Netflix and Entropy Economics have issued dueling network diagrams aimed at supporting opposing points of view on paid peering — an issue that has been hotly debated since Netflix signed a paid peering deal with Comcast earlier this year.

Netflix and Entropy Economics have issued dueling network diagrams aimed at supporting opposing points of view on paid peering — an issue that has been hotly debated since Netflix signed a paid peering deal with Comcast earlier this year.

Yet the diagrams have a striking similarity when it comes to showing how Netflix connects to Comcast.

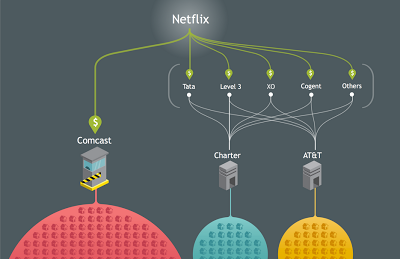

In a blog post published late last week, Netflix’s vice president of content delivery included this network diagram showing that Netflix is delivering content directly to Comcast rather than connecting to Comcast via an intermediary such as Level 3 as it does with Charter and AT&T:

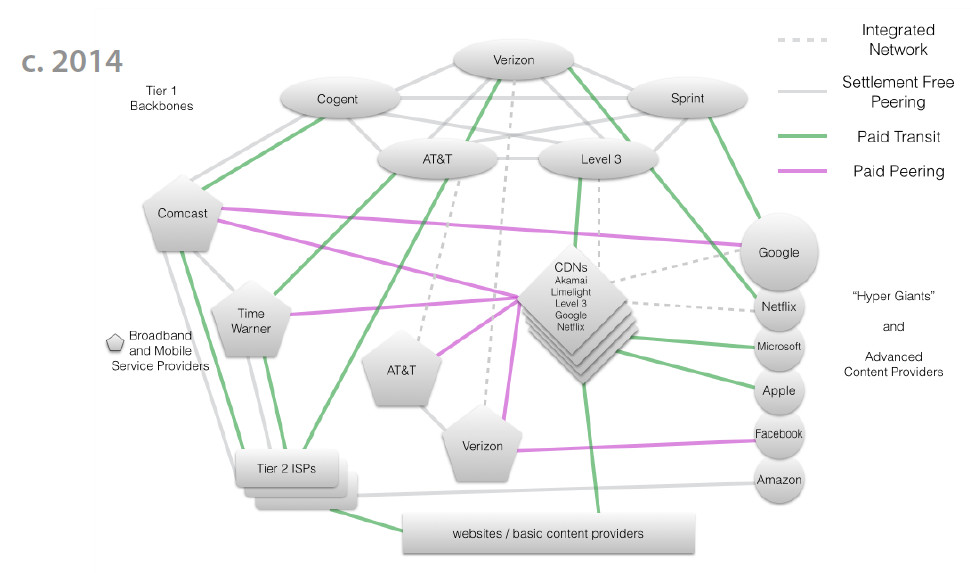

The Entropy Economics traffic exchange diagram – included in the company’s white paper titled “How the Net Works: A Brief History of Internet Interconnection” — is more complicated, but illustrates the same idea. The diagram shows Google connecting directly to Comcast, and on a call with reporters last week, Entropy Economics economist and president Bret Swanson said Google’s name could now be replaced with Netflix’s to illustrate the deal that Netflix has struck with Comcast. That diagram also shows Netflix connecting to companies like AT&T and another cable company (in this case Time Warner Cable) via an intermediary such as Level 3.

Deciphering the diagrams

Deciphering the diagrams is important, considering that Netflix this week reportedly reached a paid peering agreement with another broadband provider – Verizon – and undoubtedly is negotiating similar deals with other broadband providers, albeit begrudgingly.

So what gives?

In last week’s blog post, Netflix argued that “paying an ISP like Comcast for interconnection is not the same as paying for Internet transit. Transit networks like Level3, XO, Cogent and Tata perform two important services: (1) they carry traffic over long distances and (2) they provide access to every network on the global Internet. When Netflix connects directly to the Comcast network, Comcast is not providing either of the services typically provided by transit networks.”

Swanson’s take, on the other hand, is centered on the recognition that Netflix essentially has built its own content delivery network – a move he notes some other large content providers such as Google also have made. Content delivery networks cache content in geographically dispersed servers so that the content doesn’t have to travel far to reach customers, minimizing Internet hops and enhancing performance.

Swanson argues that some other major content delivery networks use paid peering and that it is fair for Comcast to charge Netflix for peering because Comcast receives more traffic from Netflix than it sends to Netflix. Free peering usually exists only when two network operators exchange similar amounts of traffic with one another, he notes.

So who’s right?

More things to consider

I can see some problems with both Netflix’s arguments and Entropy’s arguments.

Netflix’s argument that it shouldn’t have to pay Comcast because Comcast doesn’t carry traffic a long distance assumes that a large part of the costs of operating a network lie in the use of long-distance network assets – and that’s an oversimplification.

To gain the performance advantage it is seeking, Netflix undoubtedly is delivering traffic to Comcast at multiple points of presence at geographically disperse locations. Nevertheless Comcast still entails costs in getting content from those points of presence to end users. And when traffic volumes climb, Comcast has to upgrade the speed of the ports that it uses to connect to Netflix. (It is true, though, that this ultimately should drive customers to upgrade the speed of their monthly broadband service, yielding additional revenues for Comcast.)

Entropy’s analysis also oversimplifies certain things. For example, Swanson noted that prior to creating its own content delivery network, Netflix used content delivery providers such as Akamai and Limelight that operated servers but didn’t have their own networks.

Those companies paid network operators for connectivity. The network operators built their traffic exchange costs into what they charged the content delivery network operators for connectivity – and then the content delivery providers built their costs into what they charged Netflix.

Netflix subsequently moved its traffic to network operator Level 3, which according to Entropy had free peering agreements with major broadband providers. In the white paper, Entropy says “Netflix and Level 3 had an idea. If Netflix housed its content within Level 3, it could deliver its video to Comcast for free as if it were a peer. Level 3 would enter the CDN business and host the Netflix content for a lower price than other CDNs were charging Netflix to connect to Comcast. Level 3 would get a little extra revenue, and Netflix would cut costs by routing this traffic over Level 3’s settlement free peering links. Comcast would get the downside.”

I think it’s an oversimplification to say that Level 3 entered the CDN business just for Netflix. Netflix now apparently has shifted its traffic to its own content delivery network but Level 3 still has a CDN offering.

I would also quibble with Swanson about a comment he made on the conference call in reference to Comcast’s decision to require Level 3 to pay for peering “like other CDNs.” That’s an oversimplification as there undoubtedly are some CDN providers that don’t pay for peering.

Companies like AT&T and Verizon offer content delivery and also operate broadband access and long-distance transport networks. Both companies have traffic going downstream to their broadband customers as well as upstream from CDN customers to other network operators, which means the telcos should be able to more easily negotiate free peering deals with the other network operators.

Not all broadband access providers have their own long-distance transport networks however. Instead they have to buy transport from other network operators. And that means that, in theory, a company like Level 3 should be able to gain more free peering agreements by providing transport to some of those local or regional broadband access providers, thereby correcting traffic imbalance issues.

The upshot

It’s possible that by keeping up the pressure about traffic exchange, Netflix is hoping to pressure regulators into imposing some sort of obligations on Comcast and Time Warner Cable as a condition of approval of Comcast’s acquisition of Time Warner Cable. Now that Charter is involved in that deal as well, it may not be exempt either. And conditions written into merger approvals sometimes have a way of gaining traction beyond the merged companies.

One thing I agree with Swanson on is that regulators should tread carefully before imposing any major new traffic exchange requirements. Considering the complexity of the issue and how quickly practices change, it’s difficult even to determine what those requirements might be.

The true cost of interconnection is dependent on a wide range of factors. And only the network operators know and understand the dollar values underlying these factors.